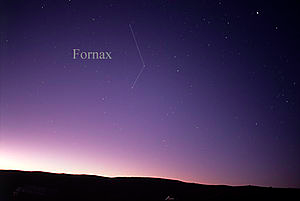

We’ve all laughed at detailed renderings of constellations overlaying a paltry set of stars that are in fact quasi-random. Like Fornax, which is just three stars:

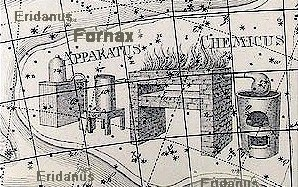

But which humans have no trouble rendering as an intricate sequence of machinery:

It would be funny, if this natural compulsion didn’t also cause us to make bad decisions, all the time.

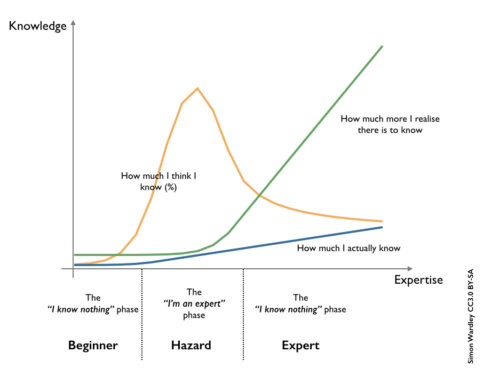

There’s a scientifically-measurable mechanism that causes us to be incorrectly confident in our knowledge and decision-making. We construct narratives of comprehension unconsciously, even when our command of the facts is feeble. Which all leads to this:

Once you realize this, you know that when you’re tackling a decision, especially one in which facts are few, you need to spend more time gathering as many facts as possible, then objectively analyze the totality, rather than forming a plausible narrative with 10% of the facts and falsely believing your theory is sound.

But this honorable behavior tends to create the opposite effect of your intention, which was to create clarity and confidence.

Rather, like clouding a stream by turning over rocks, your noble activity causes things to get murkier. Why?

Things don’t add up exactly. One “fact” contradicts another “fact,” or at least doesn’t fit into a clean narrative. This, too, is natural, because our “facts” are often crude proxies for ground truth, or opinions disguised as wisdom. Errors of uncertain magnitude are multiplied until the result is more noise than signal. The world is inconveniently complex and ambiguous.

In the face of increasing contradiction and murkiness, do you acknowledge that the situation is more complex than expected, perhaps so inscrutable as to defy analysis and explanation?

No, you fall back to your initial favorite theory, selecting the facts consistent with your convenient world-view, reinforcing your presumed wisdom, and dismissing the rest as less relevant, less impactful, less important, or less reliable.

I can prove it with a demonstration. Stop checking Twitter and dwell on the following phrase, re-reading it five times slowly and really thinking about what it means and how it makes you feel:

constricting conformity

Now answer this question: Are school uniforms a good thing?

Most people say “no,” because they’ve just been primed to think about conformity as a negative. More specifically, many more people will say “no” after being primed with that phrase than a control group that wasn’t primed.

This is one of the more robust results of experimental psychology, with consistent results over a time-span of decades. It’s also why brand-recognition advertising works (even though most people claim “advertising doesn’t work on me”).

This is why additional fact-finding doesn’t lead to improved narratives. You accidentally self-prime with your hypothesis, your initial findings, your basket of biases, the understandable preference to be “proven right” rather than admitting a difficult truth.

In fact, uniforms are often liberating. Uniforms obscure a student’s socio-economic position, which removes one of the dimensions used for segregation, bullying, and the sense of self-worth. But, being primed, and in possession of a convenient narrative, the natural response is to quickly settle on the nearest available perspective.

It’s even worse, because this effect also biases your ability to reason about numbers.

In a famous experiment by Nobel Prize winners Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky, each subject was asked to spin a “Wheel of Fortune” that displayed numbers from 1 to 100. The number they landed on was obviously random. Then the subject was asked to estimate the number of countries in Africa. This was compared to a control group who were asked the same question but never shown The Wheel. Subjects who received low numbers from The Wheel guessed lower than the control, and those who saw high numbers guessed higher!

If even our numerical sensibility can be biased by such a meaningless trick, how can we work consciously to avoid the trap?

Here are three things you can do.

Decide how to decide, ahead of time

Determine ahead of time how you are going to analyze the question, and perhaps (if the problem space is well-understood), how the analysis will determine the answer.

Examples:

To determine whether a person might be a good manager, you don’t want to start with your first impression. The right way is to ask yourself “what are the attributes of a great manager,” (this list for example), then seek to understand whether a person exhibits those attributes. Perhaps you’d decide the answer is “yes” if the person scores highly on at least 70% of those attributes, and doesn’t score extremely poorly on any one attribute. (It’s best to hire based on the value of someone’s strengths, and veto only if a weakness is excessive and relevant.)

To run a quality discussion in a meeting, you don’t want to start in the usual way, setting context and framing the debate. This generates snap-judgements instead of contemplative thoughts. Worse, initial ideas will excessively influence the remainder of the debate. Instead, send the background information ahead of time, so people can digest and form independent opinions. It is that diversity of opinions that are valuable to a discussion. Changing your mind through debate is healthy and valuable; having it changed for you unwittingly is not.

Pre-mortems

The “pre-mortem” is a technique that not only has a body of research supporting the claim that it’s effective, but is also fun to do, especially as a group exercise.

Here’s the idea: Imagine it’s a year from now, and whatever this decision is (e.g. person you hired, project you embarked on), is an unmitigated disaster. It’s a huge waste of time and money, people are pissed off, and the original objectives are a dim memory. Question: What went wrong?

The exercise is to think of what could have happened. Examples: “We thought we hired a culture fit, but they weren’t, but we let them rampage around for nine months doing damage.” “We thought the external consultant would accelerate the project, but they sucked out all our time and budget and still didn’t deliver workable code.”

Normally pre-mortems are used for projects, and the result is that you change how you work to mitigate the risk. In the example of the culture-fit, you decide to formally check in with new hires every two weeks on the subject, and fire fast if there’s a problem that can’t be solved. In the case of the external consultant, you ensure the contract allows you to terminate early, you share your concerns with them ahead of time so they understand what you’re on the lookout for, and you break tasks into small pieces so you can assess progress more continuously.

That’s already good advice, but also you can use this technique to combat the problem of biased in decision-making and data. There are studies that show that when people are explicitly confronted with contravening data but in a constructive fashion, they’ll actually listen and their biases are substantially muted. The pre-mortem fills exactly this role.

Create the space to have an insight

You cannot make complex mental connections while being interrupted by email, or even if you’re worried that by not checking email you might be missing something important.

You need open, uncluttered space for new thoughts to arise. How many stories have you read where a scientist, a business-person, an artist, is wrestling with a potentially unsolvable problem, when a flash of insight yields the answer?

And what were those people doing when the flash comes? Responding to tweets? Scrolling through Facebook posts? In a “scheduled two hour ‘think time’ window?” In an “off-site?”

No, it’s while walking in nature, or in the shower, or in a dream, or some other state of unstructured, quiet space.

This takes an investment in time, which is always in short supply. And most decisions aren’t important enough to deserve this sort of investment. But when it’s important, or when you’re going to occupy six people for two hours in a meeting, it’s worth the investment.

Most of the time, the insight doesn’t come. There might not be a rational explanation for your observations; if there is one, you can’t force yourself to find it. Genius-level physicists for more than a hundred years have been trying to comprehend how something can be both a particle and a wave at the same time, and they still haven’t had the insight. Richard Feynman once said, “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.”

Maybe your puzzle is equally inexplicable. If so, it’s better to acknowledge that, rather than to press forward with a theory that sounds good but is likely false. You can instead proceed in a different manner, where the goal is to unveil the truth through experimentation, lean methodologies, and other processes that cope well with uncertainty.

It’s better to be a humble explorer than to be confident in ignorance.

4 responses to “Avoiding the trap of low-knowledge, high-confidence theories”

Nicely done, Jason! (Now looking for a 2×4 to smack those in the ‘hazard’ group :)

And what were those people doing when the flash comes? Responding to tweets? Scrolling through Facebook posts? In a “scheduled two hour ‘think time’ window?” In an “off-site?”

No, it’s while walking in nature, or in the shower, or in a dream, or some other state of unstructured, quiet space.

Other claims in the article mention corroborating studies, do there exist similar for this claim?

Good post. Satya Nadella apparently also said something roughly similar to your last sentence. Paraphrased, it was, “Don’t be a know-it-all; be a learn-it-all.”

Source: https://www.inc.com/justin-bariso/microsofts-ceo-just-gave-some-brilliant-career-advice-here-it-is-in-one-sentence.html

“how much I think I know curve” should be upward sloping at the end. otherwise it implies confidence decreases as knowledge increases which isn’t the case.

also, “how much i actually know” should be exponential and then taper because solid foundations accelerate your ability to pick up advanced material but once you reach the top of your field, it’s difficult to go further in new territory.

i was the best in the world in an RTS game for 3 yrs and exited because there was no rival. everyone studied my moves, copied them, but could not top me because my strategies and tactics evolved in real-time whereas they were just following a set of rules from pre-existing methodologies. in that case, i recognized the infinite possibility of evolution. but it wasn’t so much that there was more to learn. it’s that new combinations of possible moves and counters could potentially appear if someone reached my level. i was tired of waiting and disappointed the only person that came close was someone who copied my moves almost exactly, so i left. “how much i think i know” should end up like a bimodal curve and with a higher peak than the original once you’re at the top of your field.