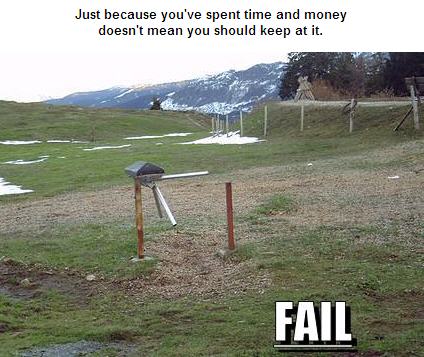

Many of my mistakes can be traced back to a failure to recognize and appreciate “sunk cost.”

The term comes from economics: “Sunk Cost” is money you’ve already spent and cannot get back no matter what. A “rational actor,” as economists say, will completely ignore sunk costs when making decisions because the money is gone no matter what action is taken next.

Of course we carbon-based life forms can rarely be described as “rational,” especially when it comes to ignoring sunk costs. It’s hard to abandon projects in which you’ve poured time and money, especially when you’ve also attached your ego and reputation.

Sometimes it’s easy to do the right thing. For example, let’s say you designed a banner ad for a certain website (cost: $1000) and paid to run the ad for three months (cost: $2000). At the end of the three months, you look at the results and they’re horrible — barely anyone clicked the ad and none of those people made a purchase.

Clearly you won’t spend any more time or money on that ad. Yes you spent $3000, but that’s a “sunk cost” — you cannot get that money back. Whether you had spent $30 or $30,000, it still wouldn’t be worth continuing this project. Obvious!

And yet, throwing good money after bad is exactly what we do in many other situations. Here’s a typical business example. A company is building a new $20 million manufacturing plant. They burn through the $20m, but it now it’s clear that it will take another $10m to complete the project. In the meantime, an opportunity has appeared where they could take over and retrofit a different manufacturing plant for only $2m.

From a completely rational perspective, they should abandon the original project. The $20m they’ve spent can’t be recovered (let’s say), so it’s now just a choice between spending $2m or $10m. Duh.

Of course the correct decision probably won’t be made. You can imagine the internal politics of someone standing up and staying “I’m responsible for this hugely wasteful endeavor, and now I want you to trust my judgment as I pull the plug and do something completely different.”

Here’s where you expect me to say how stupid big-business is and how little startups are smart and agile and never make mistakes like that, but that’s crap.

It’s not just politics, it’s human nature. Depending on which way you approach it, the term is “Loss Aversion” or the “Endowment Effect,” subtly different but close enough for our purposes.

In short: We place excessive value on that which we own, or which we perceive we own. There’s all sorts of fun experiments demonstrating this:

- At Duke University there are far more students wanting to attend games than there are tickets, so a complex lottery system determines who gets the precious few. Experimenters posing as scalpers determined that those who lost the lottery would on average pay $170 for a ticket. When they approached students who won the lottery, they were willing to part with the ticket for an average $2,400. Both students went through the same effort to get tickets, but those who own these (randomly-assigned) tickets ascribed a much larger value to them.

- Horse bettors who have already placed their bets (a sunk cost, “owning” a particular outcome) are more optimistic about their chances of winning then those who are still in line to place bets.

- Most people will not walk out of a movie they hate, because that would “waste money,” even though the money cannot be recovered and they could be doing something more enjoyable.

- Just touching an item in a store makes you more likely to purchase it.

It’s one of those things so deeply ingrained that it’s hard to change your gut reaction even when you’re aware of the problem. But that’s exactly why you have to be especially vigilant.

So where in my life of startups has this crept up and bit me? And possibly you too?

- You’ve created an awesome feature. It was hard to implement and you’re proud of it. Problem is, it turns out your customers don’t care about it, and it’s starting to create confusion and cause bugs. It’s hard to kill your pet feature, especially after all this effort, and after all customer XYZ agrees that it’s super neat-o. But that effort is sunk whether or not it’s the right fit for your product; kill the feature.

- After hours of brainstorming, arguing, and banana daiquiris, you’ve finally come up with a clever, fun, catchy marketing slogan. Problem is, it doesn’t quite fit the business. You don’t want to “waste” this great concept; surely you can use it somehow, somewhere? No. As with all writing, you have to learn how to throw things out.

- Your newest hire isn’t working out. You did everything you could during the interview; he passed all the tests. Still, he’s not a culture fit, he’s not picking things up as fast as you’d like, and everyone else is having to pick up the slack, which they resent. But, you think, it was so much work finding him and we’ve put all this effort into training him; maybe he’ll change? But he won’t, and deep down you know that. You can’t get that time back, and yes this is one of the most expensive mistakes you can make, but even worse is prolonging the inevitable. (It’s bad for the employee too — he deserves a chance to find a job where he can be successful.)

- You try a marketing effort and it doesn’t work. That’s OK, that’s what A/B tests are for! So you test a pair, and the second one is a little better but not much. And then you iterate again, and again, and …. again …. When will you stop and realize that sometimes incremental iteration isn’t enough?

- You’re trying to land a 500-seat sale with a big-name company. The trial has gone on for 9 months. They keep finding reasons they can’t buy — “deal-breaker” features they need, “critical” bugs they can’t work around, budget allocations that never materialize. But that sale would mean so much, and besides you’ve already spent hundreds of hours with them and added all these special features so surely they’ll buy from you eventually! But in my experience they often won’t, or they’ll buy just 10 seats so you can’t claim they’re “still trialing.” All this is just an indicator that you don’t have a good fit; this time-suck isn’t going to vanish once they buy. Let it go. You need profitable customers, not just customers.

- You went to school for Biology, so clearly you have to have a career in Biology! Nevermind that you made that career choice when you were a teenager and hadn’t really discovered who you were, what makes you happy, or where your talents lie. Your friends and family expect you to get a job as a lab rat and regale them with stories about diseased bovine spleens while everyone’s eating meatloaf. Should you really throw away all that work and all those expectations to follow your true dream of becoming a caterer?

It’s perfectly natural to feel attached to your sunk costs. It sucks to acknowledge that you’ve wasted time, money, energy, and reputation.

But it’s even worse to irrationally prolong the waste.

Do you have stories or advice about sunk costs? Leave a comment and join the conversation!

52 responses to “Sunk Costs: An invisible, pervasive peril”

Great post, Jason!

There’s a difference between continuing to invest in sunk costs that are clearly failures, and learning from your failures. The challenge is that both of these paths might cost time and money, but only one is fruitful.

.-= Robby Slaughter’s latest blog post: Victim One Day, Winner The Next =-.

How do you know which path you’re on?

Isn’t that the subject of your next blog post?

A good example is the classic rant on “single worst strategic mistake that any software company can make.”

Is old, bad code a sunk cost or not?

Or is characterizing everything in black and white really not such a great idea?

.-= Robby Slaughter’s latest blog post: Victim One Day, Winner The Next =-.

your example of politics around the manufacturing plant plays true in startups too, where a CEO makes a big push and then realizes that he (or she) could have a massive credibility problem with investors when the failure is evident. The key to avoiding this is not just lean (sometimes you have to make a bigger bet), but constant 2-way communication and expectations-setting.

.-= Giff’s latest blog post: Unspoken Truths: the game of industry research =-.

Great eye opener :) Thanks for posting this! I loved the “Most people will not walk out of a movie they hate”… how about “Most people will not stop eating, even if they are full, when offered a free lunch”

“There’s still time to change the road your on” – Robert Plant

Excellent post! I could’ve used this post back in 2006… Long story short, Biology major at UT for 3.5 yrs, lacked the resolve to switch to my true passion: technology (wanted to recover those sunk costs by starting a career in the health care field), finally stopped being irrational & ignoring the obvious & i’m currently a CS student, happily building my first application/startup. I’ve never looked back

The nice thing about careers is that you can still carry some value across to your next career in terms of transferable skills – at least that’s what I’m hoping to convince my next employer of!

I believe that a big piece of this comes from connecting our beliefs about failure with our willingness to assess our results and even change our behavior.

If we believe that the failure of an effort, investment of time/money or a goal means that “I am a failure” – then we will resist any assessment that leads to that belief.

If we can redefine our belief around failure to something that feels better, for example – “There is no failure, only feedback,” then we become much more willing to look at our results objectively. And act accordingly by changing our habits, our choices, even our path in life.

.-= Debra Russell’s latest blog post: Artist’s EDGE Survey Results! =-.

It’s hard to cut your losses after spending both time and money down a particular path. I think it has to do with ego and not wanting to fail.

We used to have this saying at my old company that seems relevant here:

“We are just one specification away from perfection.”

It’s a bit glib but I think people feel that if they just do this one last thing, everything will magically work out. In the end, it never works that way. Sometimes you have to cut your losses and move on or switch directions when conditions warrant.

.-= Jarie Bolander’s latest blog post: How to Divide up Founders Equity =-.

Great post. Even though I get the basic concept I still make these irrational mistakes all the time. Vigilance is indeed the key (I hope).

How true…luckily not the Biology part for me. I did Computer Sc engineering for my grad but am doing marketing right now which is so far removed from anything technical that I was taught.

I can particularly relate to the marketing example of “waste this great concept” — I was particularly bad with it when I was starting off. So I put up a poster on the wall right in front of me reading — “Love an idea but do not get obsessed with it.” Guess that helped :)

Yeah I struggle with that one too, especially in writing these blog posts.

One technique I’ve found handy is to take those “gems” and put them in another file instead of deleting them. Then I feel like I’ve “saved” it for reuse.

Of course I almost never end up using that stuff, ever. But it feels good, sort of like writing an angry letter to someone in Word and deleting it rather than sending.

Thanks, Jason!

Funny, I’d just thrown out a feature that I thought would be defining, but finishing the implementation would have been a years-long project. I did something much simpler and got 99% of the real world goals instead.

I think of hosting costs are “sunk,” too. I’d wager the majority of sites on expensive plans are preparing for a traffic tsunami that will likely never happen. I know I’ve fallen in that trap repeatedly over the last few months. :-)

.-= Mike Johnson’s latest blog post: Leemba Update =-.

Great examples, but horse betting stands out as the most “rational” reason for this pitfall. People think that because they’ve already failed, things will turn out better. Try the slot machine one more time! I think some people interpret this kind of situation as “learning from mistakes” because of the elimination of chance to fail, but they never realize they have not yet made a mistake to learn from. Eventually they cross over some boundary into mistake-land and its too late by then.

Ooo — I like the slot machine example — that’s maybe the best possible example of sunk cost. “I’ve been feeding dollars into this sucker for hours. It’s due!” Yeah.

“As with all writing, you have to learn how to throw things out.”

Good writing doesn’t mean discarding 99 out of 100 pages, it just means publishing the good ones. Ideas are the same: use the promising ones, save the rest – they may become something more in time.

This is what it really comes down to: Sunk Costs = Time, money, sacrifice, sweat, tears etc! When should the plug be pulled? Here is something that was created and is your baby and it’s just not working! I’ve never gone through this myself, let along started a new company! This has to be excruciatingly painful to go through.

What about all those stories about people never giving up, even when all looked lost, finally succeeding… :)

It’s not about not giving up because of setbacks. It’s about giving up when the ONLY reason you’re continuing is “well, we’ve come this far” even when there’s a clear alternative.

Of course, in reality, things are rarely ever clear enough. If they are, then the risk transforms into “out of all the others who see the ‘clear’ opportunity, what are my chances of being successful”.. (not that everything has to be a race, but…)

I think it is also a danger sign when people start seeing clear alternatives. It is the “grass looks greener over there” fairytale. Lack of having enough knowledge creates such illusions.

Great point about ignorance leading to the “grass is greener” syndrome. I completely agree.

Hi Jason,

Just discovered your blog. Great stuff.

One thing I’ve discovered from working with entrepreneurs is that they are like the ghosts in Sixth Sense…

They just see what they want to see.

Sunk costs bit me pretty hard in my current startup. My idea was originally centered around a violently themed, gps-based game. I believe the idea had been rattling in the back of my skull in some form since high school.

My problem was I wasn’t in high school any longer – and I couldn’t build any passion for the concept. Force of habit made me pour lots of hard work in anyhow – even after I knew there were problems.

I eventually stepped back to examine my discomfort. Once I took a deep look, I changed direction.

I stuck with gps and many of the same concepts. But the startup now fits who I am now – essential when planning for the long haul. Of equal importance: the idea itself now works far better in supporting revenue.

.-= Mike Schoeffler’s latest blog post: Ok to root for a Canadian? =-.

Even understanding sunk costs does not protect you from this dang psychological habit! It’s a killer. You have to be real brutally honest and humble.

.-= Joshua U’s latest blog post: What Men Want in Women =-.

I completely agree. I still make these kinds of mistakes constantly. Maybe if we can be conscious of the bigger, more costly ones, that’s something.,

I did spent time and money which was waste when graduating in Production Technology when I was obsessed about computers and technology. My “Sunk cost” was college fees.

I was about to make another mistake of moving to “content writing” and “marketing” where I am not good at. Somehow I managed to cancel the decision and got back to programming as I am good at it.

Anyway, Nice Post Jason !

I think entrepreneurs and business people have to seriously look at themselves when they are building companies and/or products and fall into this scenario. It struck me that you talked around this a little which surprised me and I am curious as to why. I don’t mean when the going gets tough give up, but just that you may have an idea that doesn’t pan out from a business perspective, so why keep going at it.

Your 500 seat sale example resonates. There is a well known saying in sales “If you are going to lose, lose early” totally applies here.

That’s a good criticism. Here’s why I didn’t talk about abandoning your company completely:

A wooden ship goes around the world, and during its journey the slats rot and are replaced. By the time it makes it around, every single board has been replaced. Is it the same ship? Did “it” really go around the world?

To me this is like a company who changes everything in its first two years and finally makes it out. Is it the “same company” if it’s a completely different idea and product?

What I’m trying to say is that this is a bigger question of what you do with your life, rather than saying “this company or idea failed,” though of course you DO have to make those determinations.

And, I’d like to write about that too one of these days, so I guess I’m saving my powder on that one. :-)

It is amazing how as humans we continue to pour good money after back in almost everything we do on a day to day basis. Thanks for point this out so eloquently!

I need this reminder at least once a month.

Great article, Jason. It’s all about finding the balance between learning from mistakes, determining whether those mistakes might be reversed by continuing or abandoning, and looking forward.

As you said, human nature means that it’s hard to walk away from something you’ve invested a lot of time, effort or money into. The difficult call to make is whether to throw good after bad (and see something through – it might prevail, after all) or to draw the proverbial line in the sand…

.-= John Clark’s latest blog post: Save money: invest in a big display =-.

You need to read The Dip by Seth Godin. The entire book talks about when to quit and when to stick with what your doing.

.-= Manasseh Israel’s latest blog post: 58 Degrees =-.

I did read The Dip. Still not sure when to quit and when to keep going though…

Actually, I just ordered ‘Purple Cow’ yesterday from Amazon, and I meant to add that to the order too… dang, time to spend more money :)

.-= John Clark’s latest blog post: Save money: invest in a big display =-.

Read Seth Godin’s The Dip. The most successful people are those who are smart quitters.

I did read The Dip.

The problem is his message is like a Horoscope: You should know when to quit: When you want to quit you must push through to become great, unless really you should quit in which case you must be smart enough to realize that.

Well yeah, of course sometimes it’s good to push through and sometimes it’s wise to quit. The problem is knowing which is which at the time, not in hindsight.

After reading the book, I have no idea which is which. Do you?

great read

makes alot of sense, I can relate it it right now to a girl i was seeing and i’m pumping in a lot of time/energy/cash now after things have winded down hoping for something to come out of when deep down i know its a waste……

very interesting article and i can definately relate see previous projects having a sunk cost.. i was working on a project not so long ago that had various dev teams working on it, but the code was massively flawed and full of bugs, so one day i got a phone call to say not to bother coming in. I’m still chasing for a months pay, but that was nothing in terms of how much money was wasted on development!

sometimes I think those Seth Godin books are just riddles to keep us pondering long enough until his next book comes out :)

As you say, the idea of sunk costs applies very much to writing. You have to learn to ‘kill your darlings’ as a writer, especially if you do commercial rather than creative work. If an editor or a client wants copy changed to say something else or have a different style, it doesn’t matter how much you like what you have already written, how long it will take to re-do it or how bad your ego feels. He who pays the piper and all that. But even when I write this and agree with the sentiment, I hate to do it.

.-= Matthew Stibbe (Bad Language blog)’s latest blog post: The best plays in London – Jerusalem and Twelfth Night =-.

So do you, or do you not, consider the sunk costs in cost / benefit calculation? Ironically, if you don’t include sunk costs, ratiometric evaluations make continuing on with the lousy project look relatively better than if you put the sunk cost into the ratio. Lets say we have two choices:

Option A: Cost = 10, Benefit = 100, B / C = 10

Option B: Cost = 10, Benefit = 60, B / C = 6

Obviously, you would go with option A initially.

But, after spending 5 on project A, you realize total cost will be 20. Is your benefit cost ratio now going to be…

B / C = 100 / 20 = 5, or

B / C = 100 / 15 = 6.67.

This is a real problem in project portfolio management. Some will tell you to only use remaining costs while others will say you should use total costs. Obviously, other factors besides the simple cost benefit ratio needs to be considered, but it seems odd that ignoring the sunk costs seems to encourage sticking to the original plan.

.-= Greg Burneske’s latest blog post: Earned Value Management for Product Development Projects =-.

Ah, but your math is wrong, because you’re committing the sunk-cost fallacy again!

You said that after 5 units of work you realize project A will take a total of 20 points. If you knew that from the start, then your math is correct and you would have done B.

But it’s no longer the start. The correct math is to ask whether the remaining 15 units of work is worth the 100 payout, so it’s definitely a ratio of 6.67. Which means it’s still marginally better than the other project.

However, still this math is wrong, because you’re assume there’s zero benefit so far AND no recouping of costs. Sometimes that’s true, often it’s not. Either way you need to account for the value earned so far.