Guest post by Ben Yoskovitz, the co-author of Lean Analytics, a new book on how to use analytics successfully in your business. Ben is currently VP Product at GoInstant, which was acquired by Salesforce in 2012. He blogs regularly at Instigator Blog and can be followed @byosko.

Have you pivoted before? Probably.

Was it a lazy pivot? Hopefully not.

Unfortunately, due in part to the popularity of Lean Startup and the concepts it promotes, the pivot has been bastardized to the point where it doesn’t mean much to people anymore. We hear the word “pivot” and groan or shrug, knowing there’s a good chance that people are using the pivot as an excuse.

We know entrepreneurs are delusional. It’s part of our very nature. We surround ourselves with a reality distortion field that allows us to survive the rigors of startup life and believe, in our heart of hearts, that what we’re creating and envisioning is going to succeed. We have to go into the world and convince others of the same thing–customers, investors, partners, employees and so on. In absence of proof, we rely on our delusion and reality distortion field to help propel us forward.

But when your reality distortion field is impenetrable and you’re at the point where you can’t separate fact from fiction, you’ll crash and burn in a horrible way. It happens to most of us. And it’s painful.

Lean Startup pokes a hole in our reality distortion field. It provides a necessary dose of intellectual honesty that enables us to miss the wall (or hit it a bit less painfully) and adapt. To pivot.

So, what is a pivot?

Here’s how I define it: A pivot is a shift in one aspect of your startup’s focus based on validated learning.

If you’re changing your entire business that’s a do-over. Starting over is fine, but it’s not really a pivot (and incidentally, you still won’t succeed unless you’re starting over with some insight that guides you). A pivot is much more narrow than a do-over — and it starts with having learned something. It’s what we call “validated learning”. You pivot when you know where you’re pivoting and why. You’ve gained an insight through your efforts (working through the Lean Startup methodology) that tells you what direction to point yourself.

Validated learning

Validated learning is at the heart of Lean Startup. It starts with a hypothesis, followed by a test to prove or disprove the hypothesis. You use analytics to measure the results of your experiments. Let’s use Backupify as an example.

Backupify provides online backup storage. They may not have been rigorously following Lean Startup from the get-go, but founder Robert May was testing his ideas right from the start. “Initially, we focused on site visitors, because we just wanted to get people to our site,” he said. “Then we focused on trials, because we needed people testing out our product.” Their initial hypothesis could have been, “Do enough people care about online backup storage for us to continue?” The initial website and efforts to attract visitors (and getting them to sign up) was the experiment. In order to justify (to themselves) that it was worth continuing, “enough people” would ideally be defined (10 users? 100 users? 1000 users?) with some target goal.

Robert learned that enough people did care about online backup storage. But as the business matured and they started charging money, they ran into a problem. It turns out that the cost of customer acquisition for consumers was too high compared to the revenue being generated.

“In early 2010 we were paying $243 to acquire a customer, who only paid us $39 per year,” explained Robert. “Those are horrible economics. Most consumer apps get around the high acquisition costs with some sort of virality, but backup isn’t viral. So we had to pivot [from consumer sales] to go after businesses.”

Two things are important about this:

- Robert could not have learned about the poor economics until he had learned a host of other things (that people cared about online backup storage; that customers stayed engaged for a long enough period of time; etc.) Only once Backupify had figured out how to acquire customers and retain them, could Robert focus on the economics.

- Robert’s hypothesis that he could build a scalable consumer business was invalidated by the economics. The “validated” part of what Robert learned was pretty clear: the numbers just didn’t add up.

Backupify pivoted to focus on businesses and since then they’ve scaled very successfully. Businesses pay more for (essentially) the same service, and Robert can keep an eye on the core economics by looking at the ratio of Customer Acquisition Cost to Lifetime Value.

Validated learning isn’t always quantitative. Very early on in your startup, it’s most likely going to be qualitative. Qualitative feedback is messy and much harder to interpret, but it’s incredibly important. In my experience, once you’ve spoken to 10-20 people (doing well-structured customer interviews) you see patterns that give you enough insight to make decisions. You can then scale that learning by using surveys and reaching more people in a more quantitative fashion.

The “Lazy Pivot”

If you don’t have validated learning you’re pivoting blindly. That’s a “lazy pivot” and it will likely lead to failure. The lazy pivot thought process goes something like this:

“Well, this thing I’m doing isn’t really working … I’m not sure why … but this other thing looks interesting and cool, so I’ll go do that.”

Ugh. Most probably you haven’t put enough rigorous effort into your existing idea, and it certainly doesn’t sound like you have the necessary insights to move to something else. You’re jumping from one shiny object to another.

Using Lean Analytics to Pivot Successfully

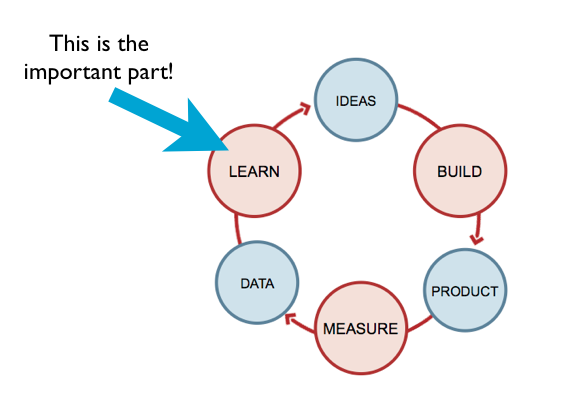

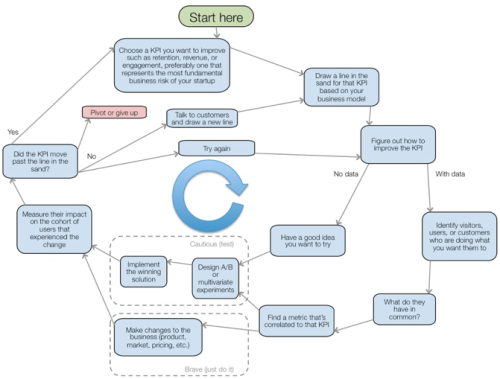

To pivot successfully you need focus and learning. You change one thing about your business –maybe it’s the business model, or pricing, or target market– and see what happens. While writing Lean Analytics, we came up with a cycle that helps explain the process of testing your idea or product, and deciding whether to pivot or not:

You can see from the Lean Analytics cycle that there’s a lot of focused attention and intellectual honesty required to test your assumptions properly and then adapt as necessary. This is a very metrics-focused approach, but you can ask yourself some higher level questions as well.

Evaluating Your Business Model

I like to use a Lean Canvas as a forcing factor to ask myself, “Do I really know what the hell I’m doing?” If you’re not familiar with Lean Canvas, you definitely need to take a look. It’s a 1-page business model tool. If you look at your Lean Canvas (which you should be able to put together in an initial 20-30 minute session), can you honestly say you’ve got enough of the answers to keep going? Do you really understand the problem you’re trying to solve? Do you really know if the solution is right? Do you understand the channels to market? Do you have an unfair advantage?

You have to go through this regular re-evaluation of your business in order to genuinely be able to make good decisions on what to do next.

Some people look at Lean Startup (and by extension Lean Analytics) and believe that it’s an entirely mechanical process, devoid of spirit, and either not effective or so effective that if they just follow the process to-the-letter, they’ll win. Neither is true. Startups aren’t built in factories on a manufacturing line. You can’t ignore your guts and passion.

Follow the Lean Canvas and use it to ask yourself if you’ve got enough information and enough confidence to move to the next step with your startup. If you’re starting right at the beginning with the problem–can you honestly say that you’ve found a problem painful enough that it’s worth solving? Have you done enough, good quality interviews with prospective customers?

One idea we proposed while writing Lean Analytics was scoring problem interviews. Since the interviews are meant to be fairly structured, it’s possible to assign scores to certain questions and get a more quantitative sense of people’s input. This may help you in your quest for validated learning, beyond using qualitative input alone.

Passion Matters

If you don’t have passion for what you’re doing, you’ll fail. The effort to succeed is too great to do it without an insane amount of caring and emotional attachment. While on occasion this is at odds with being process-focused, you have to find a way of combining your passion and guts with intellectual honesty and rigor.

So let’s say you’ve found something interesting –you have an insight based on your current business– that tells you where to pivot to. Before you automatically pivot and keep going you have to ask yourself, “Do I even care?” If you don’t, you have to reconsider whether pivoting makes sense.

I’ve met quite a few people (it’s happened to me too) that get lost in what they’re doing and they invest so much into it that they actually forget why they got into the business in the first place. That’s a scary place to be.

Before pivoting, you have to ask yourself if you’re passionate about the direction you’re heading. If the answer is yes, pivot away! If the answer is no, you need to stop. Maybe you take a step back and re-evaluate, give yourself some time to breathe and think … or maybe it’s time to quit, admit defeat, lick your wounds and come back another day to fight the fight once more.

A Quick Checklist Before Pivoting

Let’s say you’ve got some validated learning and insights in terms of what direction to pivot. And you want to pivot and keep going. What else do you need?

- Big vision. Prior to starting your company, you should have a big vision of what you’re trying to accomplish. Without that you can easily fall into the trap of building something small (a feature company) that never really has sizable potential. And pivots become meaningless if you don’t have some big, audacious goal ahead of you. A pivot is really about zigzagging towards your big vision.

- A deep understanding of the problem. Most entrepreneurs I speak with genuinely don’t understand the problem they’re trying to solve and whether or not it’s worth solving. They haven’t dug into the problem enough. Or they’re trying to solve a universal truth. If you don’t understand the problems at their core, you can’t figure out how to pivot properly.

- Actual (falsifiable) hypotheses. Validated learning isn’t enough. You need falsifiable hypotheses that you can test against, otherwise it’s very difficult to know if your pivot is going well or not.

- Metrics and lines in the sand. A core concept in Lean Analytics is around picking the right number to track and having a benchmark to compare against. You need to identify your One Metric That Matters (a single metric that tells you how things are going) and draw a line in the sand–a target that you’re aiming for. If you miss the target, you re-evaluate; if you hit the target, you have the confidence (and data!) to move to the next step.

Pivoting is hard. Check that, pivoting properly with the opportunity of succeeding is hard. You can pivot aimlessly all you want, do it lazily and hope for the best, but you’re doing yourself a disservice. Anchor your pivots in honesty and data–give yourself a chance to find a business that’s going to be fantastic.

17 responses to “The *real* pivot”

Nice post! FYI,all links are broken. :-)

Thanks for pointing out! Fixed now.

Great guest article. I think the “Lean Analytics” link in the intro is still wrong though — should be leananalyticsbook.com (the site for Alistair and Ben’s book) rather than leananalytics.com (which is parked at GoDaddy).

The top link is fixed, the bottom one is not yet.

Hooray!

the last link isnt :P

Awesomeness. There’s a reason I BM every one of these…

Really nice post. I add the blog to my ‘must read’ list right now!

Great points!