In American grade-school, we learn the “Five Ws” interrogatives: Who, What, When, Where, Why. And How. “How” is always tacked on like “Y” to the vowels. I wonder if “How” and “Y” get together to smoke cigarettes and swap stories about the indignities of being the sixth-wheel.

When investors interrogate founders, these interrogatives arise, but with a twist: Adding the word “why” in front of each. The result is a framework to help decide whether a startup is viable. It’s been explored in part by others, but given in full below.

Why is this the right team to tackle this problem? The answer isn’t “because we thought of it, and one of us can write code.” For example, suppose you have a new way to do online payments. If you don’t have experience with fraud-detection and banking systems, you’re not the right team, because those things are both specialized and difficult.

A good answer is previous experience in the industry, including easy sales contacts and insight into the language, life, and challenges of that industry (although this is also a trap). Another good answer is previous success by the team at startups, or at executing complex projects together.

Why is this question important? Because if this opportunity is as excellent as you think it is, you’ll have ten competitors five years from now, and many of them will be smart, well-funded, and carry insights of their own. If there’s a better team that can be assembled, some of them will have that team. If you don’t, you’ll be at a significant disadvantage.

What → Why this?

Why is your solution the right way to tackle the problem? There’s many possible solutions, each with trade-offs on speed-to-market, risk-of-implementation, difficulty-of-implementation, and choices in target audience, price point, and go-to-market methodology. Why is yours the right one?

A good answer minimizes time-to-market, because true learning doesn’t happen until customers are paying for something. This means creating the simplest possible solution that’s still compelling (which doesn’t mean a too-minimal shitty MVP). This probably means capitalizing on the unique experience or abilities of the founding team, choose trade-offs in things like language/framework, algorithms, UX design, and delivery platform that the team is particularly adept in and thus can create quickly and with low risk.

A similar way of thinking is to “minimize execution risk,” because early on startups are nothing but risk — risk that the product won’t work, risk that the customers won’t pay (enough), risk that you can’t economically acquire customers, risk that the market doesn’t exist, and so on. Getting to market quickly helps to minimize risk because it means you can iterate quickly against the truth. But also you de-risk by aligning the solution to the founder’s existing abilities, for example in using whatever language/framework the founders are already adept in.

When → Why now?

Why is “right now” the best time to create this startup? History is littered with startups with the right ideas, the right team, good execution, but bad timing — the market just wasn’t ready for it. PayPal failed in 2000 at its stated mission to invent a new form of currency (though it pivoted to something else), but Bitcoin seems to be succeeding in 2016. WebVan failed at grocery delivery in 2000, but InstaCart might succeed in 2016. LoudCloud invented cloud computing in 2000 but had to pivot away, but of course AWS, Google, Rackspace, Azure and others are a smashing success in 2016.

If your idea is so awesome, how come it hasn’t been done yet, or done properly? From a timing perspective, the best answer is: This idea was bad or impossible as recently as last year, but it has just now become viable. As a result, there will be a race in this space, and we believe we can win that race.

What would cause an idea to “just become viable?” Something happened in the world that removed the last blocker. Smart phones (with internet and GPS and maps) at sufficient consumer penetration make Uber and Lyft possible. Social Media makes group-games viral. Even something as simple as Pinterest turning on advertisements makes it possible to build a business optimizing those advertisements.

While the answer is often includes new technology penetrating a market, an equally good answer is that the market itself evolving. A common example is a once-stodgy, technically-illiterate industry is now populated by people toting iPads instead of clipboards.

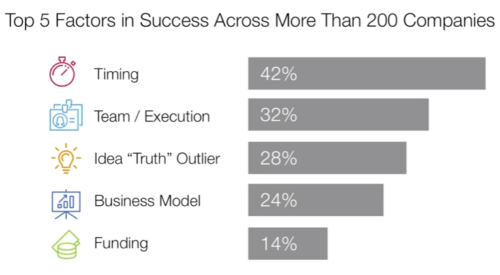

Is timing really all that important? Bill Gross examined 200 startups of all shapes, sizes, funding, and outcomes, and discovered that “timing” was the most significant factor of success — ahead of team, business model, idea, and funding.

Where → Why here?

Why should you build this startup in your current location?

You can’t swing a dead cat without someone wearily asking you for the fifth time not to swing dead cats around your co-workers. Which seems like a fair request.

But if you do swing the cat, you’ll hit someone on the Internet saying that the single best place to create a startup is “San Francisco” because that’s where all the talent and money is, or that the best place is “anywhere but San Francisco” because it’s too expensive, too much competition, and for a startup it’s better to be a large fish in a small pond instead of an ignored fish in a big pond, or that the best place is “fully distributed” because you can hire the best of the world which is both higher talent and lower cost, and not waste lives in commute-time or even getting-dressed-time.

We can all name companies with spectacular success or failure, employing any of these techniques. So the question is: Which is right for your company, and how will you take advantage of the benefits of your choice?

Why → Why do this at all?

The fact is, startups usually fail, and founders usually make less money than they could’ve in the labor market. Also it’s more painful and stressful than a real job. Also it takes ten years to build great software, not to mention a substantial company. Also it takes all your time and energy. In many ways, it makes no sense and you never know if you’re making good decisions.

So you need a solid, fundamental reason for getting into this mess. What is your true motivation? Is the journey going to be worth it even in failure? What do you want as a final outcome? Is the plan and the answers to the questions above compatible with that objective?

You also need to answer this question on behalf of your future employees. Early on it’s easy to hire, because it’s cool and fun to join a startup, and assuming you’ve hired great talent, those people never have trouble finding another job if they have to, even in a down economy.

But why will the 50th employee join? Not for the money — your salaries won’t be substantially different than their other choices. Not for the stock options — you won’t be doling out 1% of the company to anyone by then. There has to be a bigger reason. Maybe the company culture, because spending your waking hours in a place you enjoy, where you grow and have some autonomy and pride, is a wonderful contrast to most working environments. Maybe the company mission, because doing something genuinely important in the world that makes you feel good about yourself and your work, even when the work is difficult.

The Five Whys?

You might already know about “Five Whys” from Lean Startup, a method for determining root causes of problems and generating ideas for incremental improvement.

This is another set of “Five Whys,” a method for determining root motivations and justifications for creating a new company.

If you can’t answer these Five Whys in a compelling manner, perhaps your product and marketing insights haven’t yet been encoded into the form of a business. Or perhaps this is yet another case of a genuinely great idea that just can’t be made into a business. At least, not now, not by you, or not this way.

That’s OK! It just means there’s more preliminary work to be done. Better to know that now than to get too far down the path of a dead-end, so you can pick a better path and be much more likely to succeed.

5 responses to “Should this startup exist? Converting 5W’s into existential justification”

This is a really great post. Reminds me of the thinking I went through when founding my Company, Threelly (www.threelly.com). Its a lot of work and asking those why’s upfront prevents a lot of headache down the road. Thanks for sharing.

“Why will the 50th employee join?” – great question to ask.

I’m sure that it should exist ^^

I liked it

Thanks for all of these amazing resources!